Chapter Text

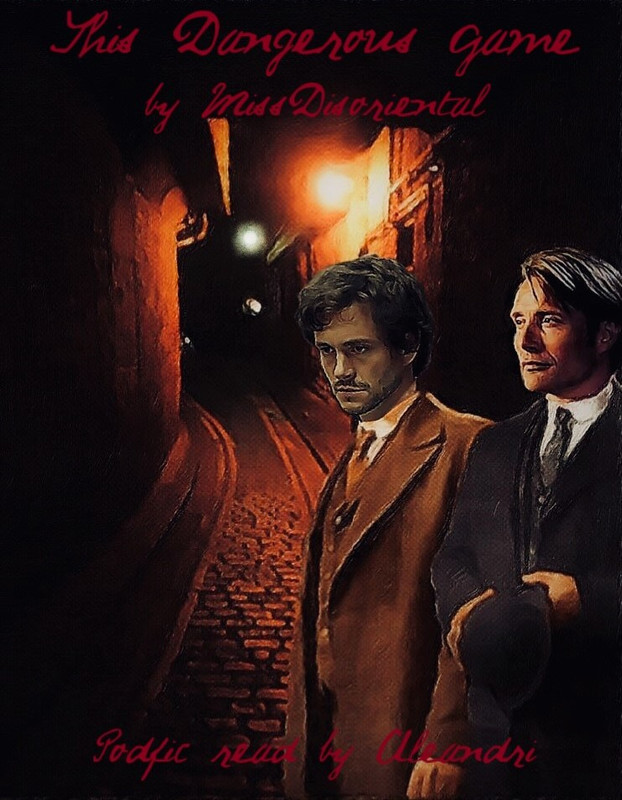

Huge thanks to the wonderful CrazyInL0v3, Petriey and marlahanni for the beautiful cover art.

28 September 1888.

Extract from a Wanted Poster produced and displayed by the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee.

GHASTLY MURDER IN THE EAST END

Another murder of a character even more diabolical than that perpetrated in Back’s Row, on Friday week, was discovered in the same neighbourhood on Saturday morning. At about six o’clock a woman was found lying a back yard at the foot of a passage leading to a lodging house in Old Brown’s Lane, Spitalfields…A lodger named Davis was going down to work at the time mentioned and found the woman lying on her back close to the flight of steps leading into the yard. Her throat was cut in a fearful manner. The woman’s body had been completely ripped open…

30 September 1888

Extract from Reynolds Newspaper.

WHERE ARE THE POLICE?

The police have exhibited an incapacity that amounts to imbecility in all their methods: and whether it is the outcome of divided counsels in high quarters or sheer incompetence, the result is the same, and a brutal murderer is given what seems absolute impunity to practise his horrid crimes…The police have failed miserably. They have obtained grace again and again from a horror-stricken public; and almost in so many words they have dared the human fiend of Whitechapel to try his hand once more…and with all their assurances he is as free as ever to pursue his hellish work, and may pursue it periodically, for aught the police can do, for years to come…

02 October 1888

Extract from The Tattle Crime.

OUTSIDE HELP SOUGHT AS SCOTLAND YARD ADMITS DEFEAT

By Freddy Lounds

After a succession of appalling and lamentable blunders – faithfully recorded in these pages with strict adherence to the facts – Scotland Yard have bowed to the force of public and civic outrage and sought outside assistance in apprehending the notorious and brutal ruffian known only as Jack the Ripper. The Tattle Crime can exclusively inform its discerning readers that the Yard have called out to the former Colonies, who were not deaf to the plea, and from which aid has been despatched accordingly in the form of a most Esteemed Expert. Mr Will Graham, late of the Baltimore City Police Force where he held the office of Inspector, is reputed to be of great acuteness in solving such fiendish outrages as these and is due to arrive in London this very week to bestow the benefit of his insight upon our overpowered constabulary. However, in a sensational twist to this darkest of tales, The Tattle Crime has learned that Mr Graham may not be quite the immaculate and upstanding official he is being represented as – and was in fact obliged to leave American shores following a series of highly questionable events…

03 October 1888

Extract from correspondence between Superintendent J. Crawford (London Metropolitan Police, Scotland Yard, London) and Doctor J. Price (St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, London).

Dear Jim, I trust you got my previous letter? Please come as soon as you can. Mr Graham has not even arrived in London yet, but has sent another rather impertinent message insisting on something he is referring to as a ‘medical profile.’ I am not entirely sure what he means by it, but it seems imprudent to dismiss it out of hand; and considering he has come so far I suppose we must extend him every courtesy. Of course I can think of no one better suited for the task than yourself. Please bring Mr Zeller with you, or any other assistant of your choice…

04 October 1888

Extract from correspondence between Commissioner K. Purnell (Baltimore Police Department, Maryland) and Superintendent J. Crawford.

Well, Jack, let us hope that this situation remains as mutually beneficial as myself and your superior officer trusted for. I suppose Mr Graham has arrived with you by now? By this time you will have been informed about the reasons why I was so little sorry to see him go; and I shall not try and deceive such an esteemed peer as yourself by pretending otherwise. Nevertheless his reputation precedes him – and notwithstanding the deeply unfortunate circumstances under which he leaves the United States, if there is anyone capable of assisting you in apprehending the perpetrator of these terrible crimes in which London finds herself ensnared, then that person is undoubtedly Will Graham…

*****

Superintendent Jack Crawford (six foot one inch; stern, impassive face; impatient manner; means well but often acts badly) runs his eye over the evening papers before flinging them across his desk in a way that is fretful and miserable and entirely out of character. He’s aiming for the wire wastepaper basket but misses by several yards and gives a wince of irritation as the pages go fluttering and spiralling into the air like a mocking pastiche of confetti. He doesn’t pick them up. The newspapers contain thousands of words, but there are several which particularly stand out and are now defiantly parading round in his peripheral vision – even closing his eyes wouldn’t be enough to erase them; they may as well be tattooed on his retina. These words are: police, failure and defeat.

Unlike the majority of his colleagues, who are inclined to see the victims as virtually asking for it (on the grounds of all being prostitutes) as well as pretty much dispensable (on the grounds of being female and poverty-stricken), Jack feels genuine grief at the idea of such horrific violence. He’s a widower and has no daughters of his own – has no children at all, for that matter – but the conceptual leap isn’t particularly great. So the flow of condemnation at the failure to catch the Whitechapel murderer touches him far more acutely than as a mere matter of professional pride. Of course it’s demoralizing to be vilified in the press – of course it is: only yesterday The Tattle Crime carried an unflattering caricature of him having a blindfold tied around his face by a grinning, leering figure obviously meant to be the Ripper himself; The Illustrated Police News published a similar cartoon the day before. But professional pride is one thing, and compassion and humanity are another; and Jack Crawford is an unusual example of a high-ranking official in ample possession of both these things.

On his desk is the correspondence from Commissioner Purnell and this is yet another thing (as if there wasn’t already enough) over which Jack is unsettled. He finds the whole concept of Will Graham – of what he is reputed to be able to do; as well as what he is alleged to have actually done – to be profoundly troubling. And although he’s embarrassed to admit it (the small-mindedness of the sentiment conflicting with the worldly, cosmopolitanism with which he likes to think he’s more than unusually endowed) the idea of a foreigner – an American – also displeases him. It would have been preferable to have kept this as a London concern, a British concern, but the scheme had been devised between Purnell and Jack’s own superior officer; and who is he to tell the Chief Superintendent of Scotland Yard what to do for the best. No doubt it’s something the Home Secretary would have been involved with too, or at least be made aware of? Well, yes, of course he’s going to be aware – questions have already been raised in Parliament about the failure to apprehend the so-called Ripper. Jack grimaces at the thought of it and runs a tired hand over his face. An American though…aren’t Americans supposed to be brash and unsophisticated? (Jack doesn’t really know; he’s never actually met any). Then he sighs heavily and rummages in his desk for the small bottle of brandy that he keeps there; ostensibly ‘for medicinal purposes,’ but really for moments like this. Of course the reality is that it hardly matters whether Will Graham is brash, or unsophisticated, or both troubled and troubling, or all of these things, or none of them; the only thing of any real consequence is whether or not he’s effective. And God knows it’s efficiency that’s needed; haven’t the newspapers said the same? Hasn’t he said the same himself? Because the bottom line is that some unholy madman is tearing innocent women apart on his watch – on the watch of Jack Crawford – and for all intents and purposes, there doesn’t seem to be anything that anyone can do to stop him.

*****

Freddy Lounds (five foot ten inches; vivid red hair like a fox’s pelt; peering bloodshot eyes and probing ink-stained fingers) is sat at his desk in breeches and shirt sleeves, punching vigorously at a creaking Underwood typewriter as if it’s done something to personally offend him. So many deadlines at the moment (dead-lines…a possible punning headline in there somewhere?), and it’s in everyone’s interests to meet them given that this recent spate of murders have been sensational for sales. Simply sensational. Indeed the interest is now international and Freddy, as well as countless newsmen like him, are doughtily determined to keep it that way. At first he’d been somewhat sceptical (“It’s only a few dead whores”) but gradually the potential was fully realised and now if he could meet the Ripper he’d shake him by the hand. The decency, or otherwise, of this sentiment doesn’t occur to him, but even if it did he wouldn’t let himself be troubled by it: Freddy doesn’t really like women (not that he’s particularly fond of men either) – an antipathy which appears to be entirely mutual. In this respect it’s not always clear from whom the aversion between Freddy (on one side) and humankind (on the other) has its origins: who fired the first shot, as it were. Like an eternal interpersonal game of chicken-and-egg.

Of course until the Ripper is obliging enough to deliver up a new dead prostitute then Freddy needs to find other ways to keep the case bubbling and simmering in the public eye. Lambasting the police has proven a convenient means of doing this, and the invective against Superintendent Crawford and co. has grown more vicious and accusatory in direct proportion to the spaces of time between each new murder. In a purely logical, pragmatic sense – and Freddy is nothing if not pragmatic – then the fact this type of killer is entirely unprecedented means the standard means of criminal investigation can’t reasonably be expected to be up to the task of catching him. But then in turn (which is also pragmatic) this is the police’s problem rather than Freddy’s.

Freddy Lounds smiles to himself and takes a sip of his coffee, which he has stingingly black and bitter, then flags down the office’s errand boy who happens to be walking past his desk. “Take these for me, would you Charlie?” he says. “Ocean Postage, mind you – they’re to go abroad.”

“Sir,” replies the boy. He glances down to where Freddy is gesturing and sees a packet of letters next to the typewriter: most, but not all, of which are addressed to the headquarters of the Baltimore City Police.

*****

Charlotte Tate (five foot four inches; wavy blonde hair the colour of pale straw; still pretty but increasingly wan and careworn) is trying to read the newspaper headlines, her lips moving very slightly as she stumbles through the unfamiliar words. The factory girls, trudging past in their print cotton dresses and neat bonnets, look askance at her tawdry attire (Bracelets! A boa!), her uncovered head (No hat!), and exchange knowing looks. These looks are seasoned with just the right amount of contempt (Oh, shocking! Shameful!), but Charlotte learnt to stop paying attention a long time ago. She doesn’t even envy them anymore; for all that their neat little bonnets signal respectability, and that the cotton frocks are stitched together with propriety and decency itself. Who would want to work in a factory? It’s the most deplorable type of drudgery: long hours, low wages; an exhausting, miserable life for next to no money. Hazardous too. There are constant stories of workers maimed and killed courtesy of faulty machinery and perilous conditions, everyone knows about them – the endless parade of blind seamstresses, and crippled textile workers, and matchmakers disfigured with phosphorous jaw. Charlotte is not miserable (at least not most of the time) and because she is young and clinging onto prettiness then the money is in reasonably ready supply: life, while not exactly kind to her, has at least been economical in its cruelty. That is not to say she wouldn’t prefer to do something else of course, given the choice. But what else is there to do? There really is very little else. Not when you are a woman, at any rate.

Charlotte knows that the screaming message in the blocky black newspaper headlines is an important one; but somehow she’s not quite willing to connect it with herself, because she doesn’t recognise her own image in the lurid descriptions of whores, harlots, and daughters of vice. A man from the Baptist society shouted that at her once: just there in the street, right in front of everyone. Some people laughed, and some looked outraged, and one or two even looked sympathetic, but it wasn’t enough to make anyone intervene on her behalf. He was wearing a shiny black suit that resembled a beetle’s carapace: a long, skittering beetle with legs and arms and religious tracts, calling her wicked names like ‘slut’ and ‘Jezebel’ until his face grew red and flecks of spittle flew out of his mouth. Charlotte didn’t say a word the entire time, but if she had she would have told him that she hadn’t planned this life, or wanted it. She would have told him how she was married once and that that the usual clichés applied just as well to her as to anyone else – how they were ‘poor but respectable’ and ‘young and in love’ and how they ‘lived decently but kept within their means.’ She could have told him – or anyone, if they’d troubled to ask – about how excited and happy they were to start their married life (because London was the pinnacle of an Empire on which the sun was alleged to never set and surely only good things could happen in such a place, especially to a couple that loved so well and so sincerely?); but how her husband had been killed in a factory accident, and how the money ran out, and that it was ultimately either die on the street or earn a living from it. She still carries a cameo of her husband: a little piece of miniature portraiture, small enough to hang in a doll’s house, which is tucked inside a tortoiseshell clasp and swings round her neck on the days she’s not working. The necklace is not there today.

He had really seemed to hate her, that beetly Baptist man, although he didn’t appear to care about the men who made the whole profession possible. At least if he did he never mentioned them. The newspapers, on the other hand, have the opposite concern. They don’t really care about the women at all; they are more preoccupied with the man. This unknown man, this ‘Jack the Ripper,’ who is killing prostitutes – even though the latter don’t appear to signify beyond the fact that they were once alive, and now they are not. They are like supporting actresses in someone else’s drama. Charlotte doesn’t notice this as either a good or a bad thing: it just is.

“Lottie!” says a voice, “Lottie! Over here!” And Charlotte turns round to see another girl, Emma – another Daughter of Vice, another Fallen Woman – with whom she used to share lodgings in the past and, in the present, occasionally shares a corner of the street. Grimly they confer over the most recent murder. The term ‘Jack the Ripper’ is already common currency: everyone knows who he is. And yet no one has any idea. Isn’t that odd?

“London’s a big place,” says Charlotte, because it’s true and it is. “What are the odds of running into him?”

“No odds at all,” replies Emma. And maybe they believe this, and maybe they don’t; but it’s easier to frame it this way because what other choice do they have? “I had to go out last night,” adds the latter, as if to confirm it. “My landlady was screaming for the rent. Said she’d throw me out if I couldn’t pay her today. She’d do it too, the hard-faced old bitch.”

“But she won’t…will she Em? You got your money?”

“That I did.” She takes a grimy paper envelope from her reticule to show to Charlotte and together they examine the copper coins inside; an embarrassment of riches. “They have eclairs in the pastry shop down Fairfax Road,” Emma adds. “I saw them this morning. We could treat ourselves.”

So the two of them links arms and proceed down the middle of the pavement, laughing gaily at nothing and ignoring the disapproving looks from the passers-by. In several decades time, psychologists will coin the term ‘cognitive dissonance’ to account for such seemingly irrational behaviour: a coping strategy for dealing with fear and inconsistency, and not at all uncommon amongst the troubled and traumatized. Although this insight will come far too late to help Charlotte or Emma, or anyone else like them.

*****

As the girls pass down the street their laughter drifts in through the window of Inspector Will Graham (late of the Baltimore City Police Force, currently of Camden Place, London; five foot nine inches; brown hair and blue eyes), who glances up and then smiles in spite of himself, because it’s so long since he heard genuine, unaffected laughter that was neither sardonic or mocking and there’s something deeply appealing in it. Not that he’s much given to laughing like that himself (he doesn’t even try and remember when the last occasion was, because frankly it’s an impossible task) but he can still appreciate it in others. It’s a bit like enjoying music whilst being unable to play an instrument yourself.

Will has the same newspapers on his desk but is trying very hard not to look at them; partly because they are extraordinarily depressing, but also because one of them has a large picture of himself on the front and the sight of his own image always makes him writhe in spasms of acute embarrassment. Instead he’s preoccupied with trying to compose a letter back home, although it’s proving an arduous task and the words won’t come. In fact in the past ten minutes he’s only managed two – Dear Father – which in the grand scheme of letter writing feels singularly unimpressive. It’s not even as if his father is particularly dear, but the grudging old bastard is going to expect communication of some kind. And besides, Will doesn’t have anyone else to write to. He glances down again at the two lone words, which almost seem to be mocking him in their insincerity. Dear Father: who is in fact not dear.

Will spins the pen into the air and neatly catches it one-handed before tucking it behind his ear. Then he pours himself a glass of water from the carafe on his desk, trying to prevaricate for just a little bit longer, and catches his reflection in the shiny surface when he places it back down. The face that stares back at him is frustratingly young and fragile looking: all wide-eyed and delicate-boned. He’s tried cultivating a beard to give himself a bit of gravitas, but isn’t entirely convinced at how successful it’s been (and in his gloomier moments is forced to concede that it shows an undeniable and unfortunate tendency towards fluffiness). Such youthfulness feels somewhat ironic, considering that if the toils of life are supposed to show on the face – which surely they ought to? – then by rights he should look well and truly fucked. Sighing slightly, he picks up the pen again.

“The passage over proved remarkably quick; only six days from New York to Liverpool. I have now arrived safely in London and am glad to say that I am already settling into life in a new country.”

The second part is a complete lie but it hardly seems to matter (anyway, Will’s skilled at lying when the situation demands it; so therefore intends to start as he means to go on). And it’s not as if he ever felt particularly settled in the old country either, so who cares anyway? In order to labour the bullshit point he adds: “In fact I anticipate being very happy here.”

“I don’t, actually,” Will tells the paper sarcastically. “I anticipate being extravagantly and excessively miserable.” Then he realises that he’s talking to himself – and that this is probably not a good habit to acquire so very early on – and so has a sip of water instead and tries to think of something to write which is suitably safe and dull. What though? He skims his eyes round the room, inadvertently catching sight of the newspaper headlines again (oh God, not those) before settling on a stack of playbills that arrived this morning from Astor’s theatre and which are enthusiastically advertising a forthcoming lecture series. It’s an odd combination: The Art of Engineering on Monday, evolutionary biology on Tuesday, and the evening after a presentation from a self-proclaimed ‘dare devil’ ("Asshole," says Will) who survived diving from the Clifton suspension bridge; for seemingly no better reason than to bore the general public rigid with the re-telling of such lethal stupidity. In this respect, he thinks, the grouping of the last two is highly ironic: bad luck Mr Darwin – natural selection doesn’t win today. He smirks to himself, then abruptly sighs out loud and reluctantly forces his attention back to the letter. Oh for God’s sake, this is ridiculous; it’s only a message to his father, why is it so difficult? Perhaps he could describe the morning’s dutiful round of sight-seeing? Trafalgar Square and the Horse Guards Parade. He’d taken a walk through St. James’s Park afterwards, admiring the Pavilion and the spread of shrubs and foliage, then shared his lunch with a stray dog that came and joined him by the lakeside. Will is fond of dogs although this is likewise something he can’t describe to his father, who detests them as dirty scavengers and would never let Will have one in the house. Will is cherishing vague hopes that he may be able to acquire one here, although given the prohibition on pets at every boarding house he enquired at it doesn’t seem very likely.

“I saw St. Paul’s cathedral this afternoon. I believe it would have interested you. The architecture is very…”

He frowns and comes to a halt. Very what? Indicative of humanity’s superstition, credulity and pathetic willingness to devolve responsibility to a spectral High Power (in effect: a big bearded man in the sky)? An utter waste of taxpayer’s money? A pretentious, swaggering piece of shit?

Carefully he writes: “very impressive.”

He puts down his pen again and gazes out the window, trying find some inspiration. The building opposite has an enormous streak of coppery-coloured damp down the side that begins at the chimney and runs the entire length of the wall. Look at it too long and it starts to bear an unfortunate resemblance to a urine stain; as if someone’s taken a piss down the side. As if it’s come down from the heavens themselves. God again? Dear Father, I am sure you would be enormously diverted by the big streak of celestial piss on the other side of the street.

Will gives a defiant smirk at the idea of the look on his father’s face if he actually did confide this particular insight, then runs his hands through his hair until it stands on end, unpins his collar and rolls up his shirt sleeves; which is probably terribly vulgar, but there’s no one to see him do it, so (once again) who cares? Not that he would care if there was someone. To compound the point he takes his boots off and flings them into the corner so he can sit there in bare feet, then earnestly tries to think of something to write that the old bastard would actually want to hear.

“The class structures here are extremely ingrained, almost ludicrously so. In this regard there are certainly things that the Old Country could learn from the egalitarianism of America.”

Not that this is really true either. Maybe blood and birth – good breeding – are of less consequence, but you hardly need to cross the Atlantic to recognize the twin pillars of money and respectability as eternally essential elements of the social contract. Will, who has never acquired money (and never aspired to respectability) feels he is in a good position to judge on these things. Although this is hardly the type of sentiment his father – who is conservative in his politics, conformist in his outlook, and aspirational in his notions of social mobility, despite having a collar of a distinctive blue hue – is going to show any kind of sympathy with. At times Will feels something like guilt for the intense contempt he harbours towards Graham Snr for such mindless submission; to Will, there’s nothing commendable or admirable in it – it’s simply a form of identifying with the oppressor.

After some thought, he adds a merry little exclamation mark at the end of the sentence (America!) to give the impression that this is something over which he and his father, as enlightened, democratic Americans, can share a private joke: sniggering secretly together at the stuffy, narrow-minded English. Not that this cosy confederacy would be at all the state of things if his father really was here: they’d have already begun cycling through the usual sequence of chronic, chafing resentment, with Will ultimately regressing into a state of adolescent petulance (the beard has never been a safeguard against this, either) and his father glowering and chewing on his moustache, which always appears as wiry and tufted as a toothbrush, before retreating into a miasma of speechless outrage. Will knows that a good portion of the discord stems from the fact that his father would have liked the type of son with whom he could sip beer and discuss the Baltimore baseball league (as opposed to a son like…him); but also from the fact he resembles his mother, who was likewise wide-eyed and delicate-boned, and that the association is a painful one from his father’s point of view. Although whether it’s the pain of grief and loss, or the more bitter pall of rage and resentment he’s never been able to fully determine, and hardly feels able to ask. They’re not on those sort of terms.

Will pauses again, fretfully gnawing on the end of the pen, and allows his eyes to stray away from the letter and roam across the detritus already littering his desk. Lying across the blotter is a note from Jack Crawford curtly requesting him to come to Scotland Yard first thing tomorrow morning. That’s it; that’s all it says. Nothing about the purpose of the visit, or what’s expected of him, or even a few trite yet well-meaning lines about being glad that Will is here…although Will isn’t glad he’s here, so maybe there’s no reason for Jack Crawford to be either? He’s still not sure how much they know about him – how much detail Commissioner Purnell went into, the exact extent of the disclosures. That whole incident following the brain fever…God, surely they can’t know everything? Although really, it hardly matters whether they know or not – because he’s still here regardless and tomorrow is going to be expected to stumble straight back into someone else’s nightmare. If he could he’d probably cry, or even scream; but is ultimately afraid to do either because of the sense that if he starts he’ll never be able to stop and will be sobbing and screaming every single day for the rest of his life. Of course there’s no doubt that the awareness of this is the true problem to be avoided; ironic, really, that prevaricating from writing the letter – that the letter itself – is merely playacting for evading the genuine source of distress. But how to even begin contemplating such a thing: a problem so huge and horrifying that it’s like a living thing; like a second person in the room? He doesn’t even have the words to discuss it with himself. If it was written down it would have to be expressed in ellipses, obscured behind a sequence of dots because the enormity of it defies both awareness and articulation: ‘The things Will Graham feels are ….’ He only know that he doesn’t want to do it – wants to go home, wants to be normal – even though wanting isn’t relevant, being little more than a form of hopelessness-by-proxy. Then a mournful, childish part of Will wants to proclaim ‘I can’t bear it’ but of course he has no choice but to bear it – and has never had a choice, and is never likely to have one – so he says nothing.

“And I’m not going to talk to myself,” Will adds (before realizing that this admirable resolution is somewhat undermined in that it does, in fact, entail talking to himself), so he inwardly rolls his eyes and returns to his letter.

“I have secured very pleasant lodgings,” he writes, “at a reasonable rate and in a convenient part of the city. The landlady has been very kind to me, and the buildings in the neighborhood are of an extremely striking aspect in the style of…” He pauses once more, and then replaces his pen on the table. In the style of what? He’s never really known all that much about beautiful things.

*****

Dr Hannibal Lecter (currently resident of an exclusive medical practice in Harley Street; previous provenance no-one-quite-knows-where; six foot one inch; dark hair and dark eyes) is also reading the newspapers, giving the occasional wince of distaste as he takes in the details of the latest atrocity in Whitechapel. Admittedly his aversion is very far removed from the kind expressed by 99% of the paper’s readership, but to him the sentiment is no less valid. In fact if anything it’s more so, because it comes from a place of genuine discernment and intellectual integrity as opposed to blindly bleating moral outrage. Slaughter such as this is almost unbearably ugly to him: brutal, mindless and pointless. Worse than that – artless. Graceless. No virtuosity at all. Hannibal gives a fastidious shudder and allows himself a small sigh at the depressing bestiality and swinishness of the populace in general. Even in a supposedly cosmopolitan and sophisticated city like London, one only need to glance out the window to seem them teeming and floundering like farmyard beasts. Oh yes, and speaking of which…

“Sir,” says a voice from outside his study, “I’m sorry to disturb you but Mr Froideveaux is here.”

“He is rather early,” replies Hannibal in a calm tone that in no way betrays the internal twinge of irritation at the interruption. In fact Mr Froideveaux is inevitably early, in a neurotic, overanxious way (tedious). Although there is no denying that he has had worst patients (not that he had them for long…as it were), and that to be consistently late would be far more objectionable, so he is prepared to tolerate it.

“Shall I show him into the consulting room?”

“If you would be so good,” says Hannibal. He refers to his watch and realises he has precisely 12 more minutes, so opts to spend them in a thoughtful examination of the second newspaper. Inspector Will Graham is rather intriguing looking; not least because he is extremely young to be in a position of such responsibility. Either he has some obliging relative who has purchased the influence on his behalf, or Inspector Graham is a perfect prodigy of the macabre. On reflection, he believes it is almost certainly the latter. Will Graham looks skittish and ill-at-ease, very far removed from the kind of strutting and swaggering which one would anticipate a privileged upstart to display before onlookers. On the contrary he’s refusing to look at the camera, rather studying the floor instead. Not fond of eye contact, then. One would think he didn’t really want to be there. And yet there he is nonetheless. How very interesting.

Hannibal, unlike Will, does not roll up his shirt sleeves or take off his collar or fling his boots across the room; although he does perform his own personal version, which is to stretch his long legs out in front of him in a manner which is far more nonchalant and casual than his usual custom before steepling his fingers beneath his chin and gazing thoughtfully into space. All the way from America too…how has such a rare plant come to be transplanted so far from its native soil? And into terrain that’s so undeniably barren and unpromising? Then he spends a few moments amusing himself with the notion of Inspector Will Graham as an actual plant, and what species it could possibly be. Firstly he cycles through the droseraceae – carnivorous plants that scour for stimulus then employ seductive snares to lure their victims in – but ultimately rejects this analogy as too coarse. Too…obvious; more suitable for Hannibal himself, if anything (smirk). A rose, then? Rosaceae. Beautiful and fragile-looking, but with a thorny underbelly that snags and tears at the unwary – at anyone who underestimates their potential for savagery. In his previous practice, he encountered a patient with a deep puncture wound acquired from a rose bush: gangrene had occurred, followed by sepsis, and the man lost first his limb, and then his life. An unusual case. Hannibal narrows his eyes, almost imperceptibly, and returns to studying the photograph.

Although he is not generally given to flights of imaginative whimsy, something about Will Graham’s sad young face has undeniably caught his attention. It’s not compassion exactly (compassion being inconvenient); more like…what? Fascination? Captivation? No, not that; not exactly. Perhaps intrigue would be more accurate. He reads the accompanying text for a second time, neatly slicing through the hyperbole to extract the underlying facts that speak to him from the photograph. Young. Lacking in confidence – and yet there’s an undeniable air of self-possession in the defiant little tilt of the jaw and the frown line between the delicate eyebrows. He still knows how to hold his own. But what exactly is it that draws such an unlikely specimen (rosaceae) into such a relentless, pitiless occupation. What exactly is the appeal? Because of course there must be one. Admittedly this is an excessive amount of conjecture to draw from a single grainy, monochrome photograph; but then Hannibal Lecter has always been extraordinarily skilled at seeing things that other people can’t; at things it would not even occur to other people to look for. And so he sees Will Graham, and he wonders.

From beneath the window comes the mournful call of the newsboy: “Terror in the East End! Read all about it! Ghastly murder in Whitechapel!” Has there been another one then? Most people would probably migrate towards the window at this point, but Hannibal is not most people so he remains where he is and gazes contemplatively at the view of the city from the confines of his chair. Dusk is beginning to descend, shrouding everything in thickly coagulated shadows that bleed into the fog. The gas in the streetlamps is already being lit; darkness is coming.

“City under siege!” calls the newsboy. “Read all about it! Fiendish murderer still at large!”

The 12 minutes are up so Hannibal stands and straightens his coat, permitting himself one final glance at the photograph. Such a sad face. Without fully thinking about it, he briefly touches his fingertip against the features (wide-eyed, delicate-boned) that gaze out from the newspaper. Later on, he will ask himself what compelled him to perform such an action and won’t be able to fully say.

“Keep your wits about you Inspector Graham,” he tells the picture. “I rather fear you are going to need them.”

*****

Tomorrow Will Graham and Hannibal Lecter are going to meet for the first time and their respective worlds are going to tilt. Jack Crawford is going to meet Will Graham, and Will Graham is going to meet Jack Crawford and in doing so discover that there are far worse things about London in the autumn of 1888 than a room with no view and no dogs. Charlotte and Emma are going to meet with Fate (if Fate isn’t too stately and solemn a term for two poverty-stricken street women for whom the world cares nothing) and Freddy Lounds and his brother journalists are going to write more newspaper articles and in doing so, without even knowing it, create what commentators in decades hence will describe as the first modern prototype for the concept of a serial killer. The public, in the meantime, are going to buy the newspapers and read the articles and then they will grow outraged; but only because these are the last remaining days before the outrage evolved into outright terror. And then the fog is going to descend again – the worst fog, people will later say, for 30 years – and the shadows will choke across the streets and dark things are going to crawl out of them. None of this has happened yet; but it will. The pieces are assembled on the board – just so – and now the game begins.

Chapter 2

Notes:

Hello my lovelies, welcome to Chapter 2. I’m guessing everyone who’s read the summary has an idea of what to expect - but just to be clear that from this chapter onwards there’ll be references to crime scene violence, both real and fictitious, that some people might find distressing.

(See the end of the chapter for more notes.)

Chapter Text

Jack Crawford is staring at Will, and Will is gazing back again whilst heroically feigning polite interest and trying to conceal the true extent to which his attention is starting to wander. He’s extremely aware of how loud the carriage clock sounds in the background, exaggeratedly heavy on every other beat: tick-tock, tick-tock. The mechanism is obviously faulty…no doubt it’ll break before too much longer (good, thinks Will; Godspeed, you annoying fucker). Then he attempts to stifle a yawn, not altogether successfully, and pushes up his glasses with his forefinger to try and hide it. Oh Christ, this is tedious. Why doesn’t Crawford say something? Will assumes it’s an attempt at a power-play, possibly outright intimidation – now look here you little upstart, you might think you’ve been wheeled in to save the day but let there be no mistake about who’s really in charge here – and wishes he could tell the older man to save their mutual time and simply not bother. After all, far more authentically frightening people have tried to overawe him before now, and they (mostly) didn’t accomplish it either.

“So.” Jack Crawford clears his throat, having apparently decided that the awkward silence has lasted sufficiently long. Will raises his eyebrows expectantly. “Here you are.”

This seems too self-evident to require confirmation, so Will just smiles politely and allows his eyes to drift to a patch of wall behind Crawford’s head while secretly thinking that if this is Scotland Yard’s idea of observational acuity then it’s not really surprising that they require outside help from the likes of him. The office is airless and stifling, the catchless windows preventing any kind of ventilation, and he wants to take his jacket off and loosen his collar but is concerned the gesture would appear too casual for a first meeting, possibly even rude; particularly when Crawford appears to set such store on protocol himself. Will sighs, almost imperceptibly, and knots his fingers together beneath the desk.

“Good journey?”

“Yes. The Atlantic crossing was remarkably fast; only six days.” He briefly considers whether he can be bothered to reproduce the carefully cultivated enthusiasm exhibited in the letter to his father (the wonders of modern engineering!) and ultimately decides – no, absolutely not.

“And then a train from Liverpool I suppose?”

Will blinks. Well obviously yes; how else was he supposed to have got here? Actually sir, I sat on my trunk and pointed it south. “That’s right,” he says earnestly. At least there’s no temptation to wax lyrical about the wonders of modern engineering in this instance; the train had been unbearably uncomfortable and Will had been miserable with motion sickness for nearly the entire journey.

“Settling in?”

“Thank you, yes.” No. Not that an honest answer is either expected or required. Really this whole stilted conversation is ridiculous. Will knows perfectly well that his presence here is little more than a carefully contrived display of quid pro quo. He himself has been exiled under a cloud of suspicion and bad feeling, and Commissioner Purnell has called in a favour from the Chief Superintendent in London – allegedly an old college friend although it’s hard to image Purnell, miserable old bastard that he is, having friends of any age or provenance – in an attempt to conceal this and rid himself of Will in a way that reflects well (or at least minimally badly) on the Baltimore force. Effectively they want to deflect attention away from what Will has done; all those…events. Scotland Yard, in turn, has already garnered a spectacular level of opprobrium for its failure to do anything substantive about the Whitechapel murderer so the presence of an American expert is a convenient bone to throw to the press. I am a bone, thinks Will gloomily. An actual bone. He sighs and peers at Jack Crawford over the top of his glasses.

“You’re younger than I thought you’d be,” says the latter, almost accusingly, as if Will’s youth is something he's arranged on purpose in order to cause maximum inconvenience.

“Right,” says Will, because – who cares anyway?

“Boyish.”

“I guess.” The Beard of Gravitas has obviously failed yet again – how typical. Will sighs to himself one more time, before realising that he's started absent-mindedly stroking it with his left hand, as if it’s an ailing pet.

“You guess! You mean you don’t know?”

“It’s a figure of sp…” Oh fuck it. He reaches over and plucks the tabloid paper from the desk instead, brandishing the stark blocky headline which is screaming out a lurid account of the most recent murder. “So,” he says. “Why is he called Jack?”

Crawford glances up sharply, as if suspecting some kind of insubordination, but Will recruits the wide eyes and young face to get off the bench and put their respective skills into play and the resulting innocent stare deflects suspicion successfully. Crawford shifts awkwardly in his chair; Will mentally gives himself a smug victory handshake.

“Well the Ripper part is obvious.”

Well – yes, thinks Will irritably, which is why I didn’t ask about that part.

“The ‘Jack’ aspect – well, he came up with that himself,” says Crawford grimly, and Will raises his eyebrows, trying to appear poised and politely interested despite the fact that every single hair on the back of his neck has just stood on end.

“The Central News Agency received a letter on September 27 signed Jack the Ripper. Here.” Crawford pushes a piece of typed paper across the desk. “The original was handwritten of course – in red ink, no less – but the transcript is exact, including the punctuation and spelling errors. It’s not the first letter to arrive claiming to come from him, but this one was different. This one we took seriously.”

“Why?”

There’s a grim pause. “Because it contained information that only the murderer would know.”

The paper is now directly in front of Will, just lying there and looking innocent enough – despite the fact that for all the horror and misery it’s going to herald it may as well be a stick of dynamite or a bottle marked with a skull and crossbones. Once I pick this up, thinks Will, a bit wildly, once I’ve read it then there’s no going back. Crawford clears his throat, obviously impatient; and Will reaches out a hand, slowly as possible, trying to delay the official start of his involvement with this living nightmare. He realises he’s now paying more attention to his hand than he is to Crawford, or even the actual letter. It’s an odd sensation: watching it reaching out, the way the fingers are flexing and jerking…like an alien thing that doesn’t belong to him as it treacherously sets the game in motion. Wincing slightly, he takes a deep breath and then begins to read:

25 Sept. 1888.

Dear Boss,

I keep on hearing the police have caught me but they wont fix me just yet. I have laughed when they look so clever and talk about being on the right track. That joke about Leather Apron gave me real fits. I am down on whores and I shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled. Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some of the proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I cant use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope ha ha. The next job I do I shall clip the lady’s ears off and send to the police officers just for jolly wouldnt you. Keep this letter back till I do a bit more work then give it out straight. My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good luck.

Yours truly

Jack the Ripper

Dont mind me giving the trade name

PS Wasn’t good enough to post this before I got all the red ink off my hands curse it No luck yet. They say I’m a doctor now. ha ha

Will frowns to himself when he gets to the end of this missive, then gazes into space for a few seconds before reading it again. The jaunty, mocking tone, the terminology: a delineation of horror that’s almost light-hearted in its levity. No, the whole thing feels…wrong. “I don’t think this is genuine,” he finally says.

Now it’s Crawford’s turn to raise his eyebrows. “Oh? And you think it’s a hoax because…?”

“Several reasons. On the basis of the scenes described to me, the type of person who’s committing these crimes wouldn’t correspond like this. It’s too organized and rational – too coherent. This letter is playacting. It’s the interpretation of an educated, articulate person of what a demented murderer ought to sound like.” As an afterthought he adds: “And it’s far too contrived. There’s no way a killer of this type would refer to the murders as ‘funny little games.’ Nor is he planning ahead to future crimes in the way described here – again, that would be too organised. He’s chaotic and impulsive; he only knows what he’s doing in the moment.”

Jack Crawford narrows his eyes. “Why are you so opposed to him being organised and rational? He’s shown enough of both capacities to completely evade capture.”

“No,” snaps Will, “he’s just been lucky. He’s extraordinarily violent and dangerous, but likewise unstable, reckless and immature. He’s not even sophisticated enough to try and conceal the bodies.”

Crawford pulls a sceptical face. “We consider that he leaves them in full view in order to taunt the police. Hence the mocking tone of the letter.”

Will shakes his head, frowning impatiently and leaning forward in his chair. “Mr Crawford, I gather from the medical report that an attempt was made to remove the head of one of the victims? Consider that for a moment. This is a man who tried to decapitate someone in the middle of the street. That indicates a level of disturbance which precludes organisation; and it’s certainly not the type of disturbance which sits down afterwards and composes a letter like this.”

“Yes, but the reference to removing her ears…”

“They weren’t removed though were they?” says Will. “I’ve seen the autopsy notes. They were damaged, yes, but not missing. The writer just made a guess – and considering the extent of the injuries he probably could have claimed pretty much anything and there would have been some sort of corresponding mark on the body. And nothing actually was sent to the police; the threat wasn’t followed through.”

“Well, no, but…”

“So why not do what he said? I gather all the mutilations are carried out when the women are already dead, so it’s not as if there was anything to prevent him. Yet he didn’t, did he? And I’m saying that the reason he didn’t is because this letter didn’t come from him.” Crawford leans back in chair, regarding Will meditatively. “Mr Crawford, I’m serious. Don’t let the investigation be overly influenced by this letter; no suspects should be eliminated on handwriting samples. And try to play it down in the press, if you can.”

“Why?”

“Because,” says Will grimly, “we don’t know what impact this sort of misrepresentation could be having on the actual killer.”

Crawford makes another uncomfortable twisting motion in his chair and Will brandishes the transcript. “You say it was sent to The Central News Agency?”

“It was.”

“Well then. I’d be extremely surprised if this didn’t turn out to be the work of an enterprising journalist.”

“Interesting,” says Crawford, and Will immediately recognises the carefully non-committal tone. It means that if Will’s proved right, Crawford can claim he supported the insight all along; and if it goes the other way then ‘of course I never encouraged such a stupid theory’ can be brandished around with equal vigour.

Will sighs inwardly. “Why ‘Leather Apron’?” is all he says.

“It was a name the local prostitutes came up with,” Crawford replies. “A boot-finisher named John Pizer. He had a history of abusive behaviour; apparently he was running some kind of extortion racket: beating the women, demanding money from them, that kind of thing. The press got hold of it and he was a promising suspect for a while but nothing actually came of it. He had an alibi for the last murder that was irrefutable.” Crawford shakes his head and briefly looks overwhelmed, no doubt reliving the disappointment of losing the only hopeful lead for putting an end to the horror of it all. “I’ll be frank with you Mr Graham, no one was prepared for something like this. It’s…” He waves his hand around, a bit helplessly. “It’s unprecedented. News of this has carried all over the world.”

Will glances at him with a newfound compassion, imagining what it must be like to wake up one morning and find yourself steering a murder investigation whose gravity and grisliness has warranted international attention. “Yes,” he says sympathetically. “I saw that the papers were covering it while I was in New York.” In fact he’s well aware that it was being reported in papers within virtually every single state, but is careful not to point this out.

“New York!” says Crawford. “That’s nothing. It’s been reported in Mexico, Jamaica, South Africa…Recently it was being written about in New Zealand.”

Will opens his mouth to say ‘Shit’ and converts it into “Shocking” at the last moment, then glances down at the clippings from The Bush Advocate which Crawford is pushing towards him and gives an involuntary shudder. The headline proclaims LONDON MURDERS; FURTHER ATROCITIES; GREAT EXCITEMENT in shrieking capital letters and he can just about make out “It is said that the mutilation of the body of the murdered woman in the Aldgate district eclipses the horrors in connection with similar outrages in Whitechapel…” before pushing them away again.

“Speaking of the media coverage,” he says after a pause. “The other reference in the letter: ‘They say I’m a doctor now.’ I suppose that’s been reported in the press?”

“Yes.”

“Because of the mutilations?”

Crawford nods.

“And do you actually believe that, or is it the journalists speculating?”

“It’s not conclusive. There’s been a difference of opinion.”

“You got my request about the medical examination?”

“I did, and it’s already been arranged. Dr Jim Price. He’s a City Police surgeon – very accomplished.”

“Good. And I’d like to be present myself.”

“That shouldn’t be a problem.” Crawford sighs slightly and shifts again in his chair. “Of course if he’d kept to his original pattern then it might have been less contested, but the manner of the current mutilations casts doubt on the nature of the first.”

“First?” says Will sharply. “What do you mean?”

“Oh, you mean you don’t know?” replies Crawford. “These current murders aren’t the only ones – there was a series early this year. Although it was largely kept out of the press.”

“How?”

“Mostly because they were spread much further apart. They didn’t obviously link together as a series, so the level of panic wasn’t the same.” He turns and rummages in a filing cabinet behind him, grunting with the effort, and retrieves a sheaf of pathologist’s photographs which he hands to Will. “I know,” he sympathetically when the latter begins to frown. “But I’m afraid you’re going to have to learn to be a bit less squeamish.”

Will shakes his head. “No – no it’s not that. It’s the photographs. They’re different. These were done by a different perpetrator.”

“There were organs removed in both cases.”

“So?”

“So you think there are more than two individuals in the same timespan running around taking people’s organs out?” Jack Crawford leans back in his chair and gives Will a condescending look. “I don’t know what you’re used to in America Mr Graham, but this is London not Medieval Europe. For God’s sake man, this is the centre of the civilised world!”

Will gives Jack a look of his own, which indicates exactly how many fucks he absolutely does not give about civilisation. “Your faith in humanity is very commendable Mr Crawford, but I’m afraid it’s misplaced. Admittedly these types of offences aren’t common, but it’s entirely plausible that more than one perpetrator is committing them simultaneously. As is obviously the case here,” he adds defiantly.

Jack drums his fingers on the table and Will stares back at him, refusing to drop his eyes first. “These photographs are of male victims. Were any of the attacks on prostitutes?”

“No, but…”

“In the East End?”

“No, but…”

“So the victim profile is completely different. A member of the London Philharmonic, a trustee at the British Museum…” Will pauses and peers incredulously at the typed pages, “…a maître d'hôtel at the Albemarle? I mean – seriously. And on the basis of these photographs the method of attack varies in numerous critical ways. These,” he brandishes the photos again, “were committed by someone who knew what they were doing. And they’re not frenzied; look how the incisions have been made. These murders were performed in a measured way with a level of care and control that’s completely absent from the current ones.”

“Very sure of yourself, aren’t you?” says Jack petulantly.

“No, I’m just sure of the evidence.”

“Well the evidence isn’t all in yet. Anyway, you’re not a doctor are you?”

Now it’s Will’s turn to look irritated. “No.”

“No medical training at all?”

“No.”

“Well then.” Jack leans back in his chair and triumphantly folds his arms over the front of his waistcoat, obviously feeling that he’s put Will in his place.

“You asked for my opinion; I’m giving it to you.”

“Yes – and I’d like you to season your opinions with a bit more caution. This…what this is. It’s something new. None of us have ever seen anything like this before.”

“I have,” says Will bleakly.

“Well, be that as it may, we still can’t be jumping to conclusions on the basis of some photographs can we?” Will grits his teeth, finding the ‘we’ to be enormously patronizing; or maybe Crawford just uses the Royal We as standard, like the Queen? “Expert consultation is needed for areas like this,” Crawford adds, and it takes a truly heroic application of self-control for Will to resist snapping: isn’t that what I’m supposed to be?

Instead he gives a rather crooked smile. “Whatever you say. Sir.”

Jack glances up again, and this time Will can’t be bothered to recruit the wide eyed, youthful faced stare in the services of feigning innocence. “Speaking of which,” says Jack peevishly “I’d like you to begin working through this list. Esteemed medical practitioners, selected by the Chief Superintendent himself. We want to canvass specialist knowledge and professional authority regarding the nature of the mutilations.” Which sounds so much like a press release that Will nearly laughs in Crawford’s face – if not for the awareness that he’s just been relegated to this menial task as punishment for the obviously rebellious ‘sir.’ The wily old bastard. Wearily he picks up the list and runs his eyes over the first few entries.

“Hannibal Lecter?” he says. “That’s a very unusual name.”

“He’s foreign,” answers Jack in a needlessly fastidious voice.

He’s foreign, mimics Will to himself in a malicious approximation of Crawford’s accent (which although undoubtedly childish is also highly amusing; so he does it again). “Oh yes, I see,” he says out loud. “Rule Britannia.” And then before Jack can admonish him for being insufficiently servile: “How do I get to Harley Street?”

“You could get there in around half an hour, if you walk fast,” says Jack waspishly. “Simple as can be. Just head towards Piccadilly Circus then up Regent Street.”

“That’s quite a lot of time for a single house call…Sir. I suppose I could get a cab?”

“Harley Street is the medical district; you’ll be able to see several of the other doctors while you’re there. And you should definitely walk. Get a bit of a sense of the city.”

“Good idea,” says Will; then leaves the building and promptly flags down a hackney carriage, not because he particularly wants one but because he can’t resist sending a mental ‘fuck off’ to that officious bastard Jack Crawford.

“American?” asks the driver when Will enquires if the cab is free. He pronounces it “‘Merican.”

“No,” says Will, just for the hell of it.

“No? Not ‘merican? Where you from then?”

Will tries to remember where it is that the Queen lives. “Windsor,” he says brightly.

“Windsor! No, you’re having me on guv'nor! You’re having me on!”

Guv'nor? “Look, just take me here please,” says Will handing over the paper with the address.

“Harley Street; you after a doctor then guv? You ill or something? You don’t look it.”

I know, I never looked it, thinks Will despairingly. He retreats into the dim, cigar-smoky depths of the cab, pressing his forehead against the cooling glass of the window pane. That was always the problem.

*****

In a grubby office in Fleet Street, Freddy Lounds is lounging at his desk idly listening to his Editor ranting about the less than stellar sales figures for the most recent edition. The Tattle Crime has its base here, as does virtually every other major periodical and newspaper; Fleet Street being the journalistic hub of the country and destined to remain so for most of the next century. It’s also sporadically commemorated in some of the more disrespectable public theatres as the home of Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street – who, despite being fictitious, featured in a series of articles last year (by Freddy) implying very strongly that he was not only real but currently operating with his cannibalistic accomplice Mrs Lovett via some of the capital’s more popular pie shops. It had briefly created quite the panic amongst their more credulous readers; Freddy smiles fondly at the memory.

“I wasn’t aware I said anything amusing,” snaps the Editor.

“No sir.”

“So, how is it,” snarls the latter, “that The London Times gets a photograph of him and The Tattle Crime doesn’t? Explain it to me Mr Lounds. Astonish me with your acumen.”

Freddy merely shrugs; a deliberately insolent gesture that would be a punishable offence, possibly even dismissible, in a younger reporter. But Freddy is a veteran, and unscrupulous with it (which in this world of sensationalism, sales and unsavoury practice is a valuable attribute to have) so the management are generally disposed to tolerate excesses in him that would be permitted in virtually no one else.

The Editor now pauses and takes a moment to inspect the picture more closely. “He’s rather photogenic isn’t he?”

Freddy shrugs again. Having never possessed any particular measure of good looks himself he tends towards despising them in other people. “I suppose so,” he finally says.

“Well that makes him more marketable,” the Editor adds in a warning voice.

“Sir,” drawls Freddy. He casts the picture a sneering look, as if youth, talent and beauty are enormously contemptible – and he’s both proud and relieved that cunning and resourcefulness have enabled him to evade such burdens himself.

“It’s a shame this maniac is only targeting women,” muses the Editor with genuine regret. “It might have been a good angle to push otherwise.” He screws up his eyes as if admiring the imaginary headlines.

“Well he is, so we can’t,” says Freddy rudely.

“So find something else then,” comes the reply. “This face will sell papers, so I want you to come up with something. The police incompetence line has done well so far but the public is going to get bored with it. They are getting bored with it. We need something new.” He brandishes the photograph in Freddy’s face so there can be no mistake as to exactly what the something new should be. “The American link adds a bit of glamour, so make sure it’s mentioned as often as possible.”

“I’m already onto it Boss. Letters have been despatched to Baltimore – on their way as we speak. I expect a reply within a fortnight. Much faster if they use the Transatlantic Cable.”

The Editor nods, finally satisfied, before observing: “You’re a good man Fred.” Of course this is not exactly what Freddy is (at least not in any commonly accepted sense of the word) and the two of them exchange a wry grin when the phrase is uttered, like people enjoying a private joke.

“Of course it may be that the rumours were exaggerated,” adds Freddy slyly. He casts a look at the Editor from under his pale eyelashes, as if daring the latter to contradict him. “It might be that Inspector Graham is a fine, upstanding citizen and has done nothing of which the British public has a right to know.”

“The British public knows what we tell it to,” says the Editor firmly. “If the rumours turn out to be exaggerated then what’s to stop us running them anyway? That’s Inspector Graham’s problem, not ours. Just write ‘allegedly’ and we’re on firm legal ground. He can’t touch us.”

“No,” agrees Freddy. “But we can touch him.” As if to demonstrate this he places his finger over the picture of Will’s face, an unknowingly mocking counterpoint to the way Hannibal performed the same gesture less than 24 hours ago. His fingers are damp with newspaper ink, and when he takes his hand away Will’s features have been obscured beneath a black smear.

“Exaggerated or not – we go to press,” affirms the Editor. He nods again, then claps Freddy on the shoulder and prepares to depart to his own office, taking the occasional detour on the way to see if there are any other staff members whom he can usefully terrorise. Freddy watches him go, a mocking smile playing round his thin lips, then returns his attention to the copy of The London Times which the Editor has left on his desk. Inspector Graham looks far less talented, prodigious or pretty when daubed with Tattle Crime ink. It’s an interesting thing…how these rumours swirl around him like smoke and which, exaggerated or not, appear destined to go to be front page news. Freddy smiles again. That’s the best part of all.

“But I suspect they’re not exaggerated,” he tells the photo softly. “Are they Will?”

*****

On route to Harley Street, the subject of these reflections is slumped back against the greasy leather of the seat and staring mindlessly out of the window as the carriage clatters over the cobbles toward his destination. God knows how he’s going to get home again; no doubt this was all part of Jack Crawford’s revenge ploy. One of the cab window panes is broken, which Will knows is a punishable offence under The Public Health Act (or something) which ought to be reported; but in an aimless display of rebellion opts to show solidarity with the lawless and refuse to mention it.

Even though he suspects he’s probably being overly resentful, possibly even petty, he can’t help smarting over Crawford’s refusal to take his suggestion of two distinct perpetrators seriously. Perhaps it wouldn’t be so galling if there was a level of uncertainty, but Will knows that he’s right – preposterous to think that the same person is responsible for both. The second set targeting wretched, desperate women; the first levelled at men in positions of influence and authority. The second a turmoil of desperate escalation; the first, by Crawford’s own admission, paced and controlled and spread over a period of time. The second frenzied and intemperate; the first displaying a measure of nuance and management. A certain…flair. Will winces slightly, uncomfortably aware of what an inappropriate choice of adjective this is. It’s certainly never one that he’d share with Jack Crawford, even if – in a purely practical sense – it’s actually true. Will sighs unhappily, struck yet again by a crushing sense of injustice that he’s been forced into the position of considering human horror in these terms. It’s one of the many reasons he objected so strongly to the fawning newspaper coverage: it feels like his fate, rather than his merit, to be so proficient at what he does. And this reflection, in turn, leads to an even worse one, which is the reality of what he’s actually going to have to do – the dark labyrinths; the deranged derailment; the twists and turns; the nauseous, reeking resonance of someone else’s madness, oh God – and it takes an enormous amount of effort not to crumple against the broken window with his head in his hands. Not yet though, thinks Will, desperately trying to pull himself together. Not yet, not yet. Today he doesn’t have to do anything except speak with a succession of pompous medical practitioners who’ll no doubt offer very little in the way of insights whilst demanding an enormous amount of time and deference in return. And that while this might be bad, it’s very far from being terrible.

More for the purposes of distraction than genuine interest he takes another look at the list. Hannibal. He has a dim recollection of the name from a history class at school and frowns with the effort of trying to remember the details. Something about Alps and elephants. Although that doesn’t seem like a very likely combination…perhaps he’s mistaking it for something else. It is an odd name though; very distinctive. Memorable. In fact it makes Will feel grateful for the dull, anonymous normalcy of his own name. He has enough uncomfortable claims to idiosyncrasy – more than enough – without being labelled as such from the first seconds of introduction. There are Wills, Williams, Bills and Billies in abundance, all merging into each other and jostling over who can be the most commonplace and unremarkable. On the contrary, one would need to possess an excessive level of presence and personality to carry off a name like Hannibal; a timid, nondescript person would end up crushed under the weight of it. Then he briefly wonders whether Dr Lecter is up to the task of bearing his own Christian name before abandoning the whole train of thought on the grounds that he doesn’t actually care either way.

The house, when they eventually reach it, is far more elegant and refined than Will was expecting. In fact it hardly seems plausible that something as relatively mundane as doctoring should be conducted behind so much immaculate brickwork and graceful Georgian symmetry. He knocks briskly on the door which is promptly opened by a maidservant (at least he thinks that’s what she is – the endless designations for English domestics are rather confusing), who’s middle-aged and earnest-looking with glossy brown hair nestled under a neat little cap – and her presence surprises Will somewhat, because given the stateliness of the premises he’d half-expected something akin to a liveried footman. He doles out what he hopes is a calming yet competent smile and announces who he is, at which point the maid (or housekeeper, or…whatever) seizes the front of her apron and declares in tragic tones: “The police? Oh sir.”

Will is accustomed to this type of fretful reaction, so begins to deliver his standard speech (also calming yet competent; at least that is the plan) explaining that there is no cause to be alarmed, and that he merely wants to speak with the owner of the house. But here a second problem presents itself because the woman is clearly having difficulties with deciphering his accent and keeps repeating his statements in various states of misinterpretation (“Did you say you’ve already spoken with Dr Lecter? But I don’t think he’s expecting you; but sir, he’s still here in the house…” ) until Will feels like he’s starting to go a bit mad.

“What is going on here Mary?” asks a male voice from the darkness of the passageway.

It is a deep voice, very low and resonant with a curious smoky edge to the vowels, and while there is no hesitancy in the English it has an accent that is strongly foreign-sounding although Will can’t place where it’s from. He’s also unable to see the speaker because of the dimness of the interior and the anxious bulk of Mary, so is about to re-perform The Speech before deciding that he can’t really be bothered (not least because the voice sounds sufficiently calm and competent for all three of them), so just loudly announces his name instead. And after Mary has swivelled round and announced “It’s the police. Oh sir,” (recurring); and Will has put his hands in his pockets before realising how unprofessional this looks (so takes them out) and then remembered he doesn’t actually care about looking professional (so puts them back in again); and Mary has begun wringing her apron in both hands until there’s a real risk of it disintegrating; and Will is reflecting on a certain sense of unfairness that if she has no problem with that accent then why can’t she understand his…then the owner of the voice has moved forward and stepped out of the gloom to appear on the doorstep, at which point both Mary and Will fall silent at exactly the same time.

Will looks up (necessary because of his lower vantage point on the pavement but also owing to the speaker being unusually tall) and then blinks a few times at the sleek, imposing apparition that’s confronting him: because although he doesn’t have a clearly formed idea of what exactly he was expecting, there’s also no question that he wasn’t expecting…that. Then a brief silence follows in which no one moves or speaks and which strikes Will as somewhat eerie, as if the entire street is holding its breath. Or maybe it’s his own breath; in that moment he’s not entirely sure. And then the owner of the voice, and thus the owner of the house, and thus Dr Hannibal Lecter looks back down at him before taking a single step closer (poised and deliberate) and saying, with a slow inscrutable smile:

“So – Inspector Will Graham. What a very fateful coincidence; I would hardly have thought it possible. It appears that we are destined to meet in person after all.”

Notes:

Welcome to the History Corner – pull up a chair!

This is a reproduction of the notorious ”Dear Boss” letter which, as described here, is where the name Jack the Ripper originated. Although considered authentic for many years, it’s now generally agreed by historians to have been the work of a journalist – something also felt by many members of Scotland Yard CID at the time. I based Will’s analysis of the letter on that of John E. Douglas, creator of the FBI’s Criminal Profiling Programme and Thomas Harris’ real-life inspiration for Jack Crawford (and Bryan Fuller’s for Will Graham – including the encephalitis!). In this respect Douglas created a psychological profile for the murderer as part of an intriguing BBC documentary (‘The Secret Identity of Jack the Ripper’), and I'll be drawing from his insights during the course of this story. Which is actually all a bit meta isn't it? *head explodes*

The notion of the Whitechapel murders being copycat killings is a genuine theory amongst some historians (although the crimes in question also involved prostitutes and bear no resemblance to the ones described here). The reference to John Pizer is likewise based on historical fact, as is the uncertainty over whether ‘Jack the Ripper’ had expert anatomical knowledge. Due to the passage of time this will almost certainly remain unresolved, so from now on I’ll be putting my own slant on it.

*cough* Having said all that, this is also probably a good time to ‘fess up that I am by no means an expert on either this historical period or series of crimes. While I do as much fact checking as I have time for, mistakes are likely to creep through so apologies in advance!

Chapter Text

Will, to his infinite irritation, finds himself disarmed by this rather startling statement; and instead of responding in kind with something calmly contemplative, or dismissive (or even demanding Dr Lecter explain what the hell he’s talking about, possibly followed by “in the name of the law!” announced in ringing tones…or not), is temporarily confused into silence. As an attempt to save face he tries to give the impression that his muteness is deliberate and merely raises his eyebrows as if to imply that ‘such enigmatic poise is not having any effect on me, thank you very much, so why don’t you save that shit for someone else?’ – although the success of the strategy is negligible at best; because Hannibal Lecter is still staring at Will in a cool, considered way, and Will is finding it impossible not to stare back at him, and Mary is staring at both of them, one to the other (like someone at a tennis match), until Hannibal finally draws back slightly – not once breaking eye contact – and calmly declares: “Won’t you come in?”

“Thank you,” replies Will, relieved that someone has finally taken control of the situation even while earnestly wishing it had been him who first took the initiative. He tentatively steps inside, arching his entire body like a street lamp to avoid brushing against Dr Lecter’s coat (the latter being so tall and imposing that he seems to be absorbing every possible atom of space in the vicinity), and which is an endeavour by no means assisted by the fact that the hallway is far too narrow to comfortably accommodate three people. In the resulting confusion Will drops his hat, which Mary makes a big performance of retrieving for him whilst pompously brushing off imaginary flecks of dust, despite the hallway being immaculate with no trace of dust, dirt or other domestic disturbance to be seen. Will wishes he could tell her not to bother (in this respect much of his life seems to be comprised of wistfully reflecting on things he wishes he could do but can’t) because he hates that fucking hat – if he could he’d drop-kick the bastard thing down the street. Not that the hat is a particularly offensive example of its kind, he just hates all hats: roaming around bare-headed with collar unfastened and shirt sleeves rolled up feels far more suitable. Although he supposes it’s worse for women: all those bonnets, bodices, bustles and confining, deforming corsets; bound and trussed like delicate instruments of torture to the extent that the better-off require maids to help them dress because the task is too elaborate to accomplish unaided…and then Will realizes he has strayed off into a pointlessly rambling mental trajectory and really shouldn’t be stood in the hallway staring off into space while thinking about corsets, so clears his throat awkwardly and thanks Mary for the retrieval of the hat (even though – fuck the hat). Dr Lecter is just standing there observing the whole thing with a faint half-smile on his face.

Mary deferentially reaches around Will to close the door, which shuts with a deep, sonorous thud; and he immediately can’t help noticing how gloomy it is now the airy lightness and bustling noise of the street have been banished outside. The lack of windows doesn’t help. He supposes candles would be a bit excessive during the daytime, but really the dimness is oppressive and the faint incense-like odour puts one in mind of a crypt. Then he reproaches himself (again) for being fanciful and over-imaginative, when all that’s really happening is that he’s stood in an inadequately-lit hallway in one of the more exclusive districts of London with the smell of cleaning wax tickling his nostrils. Dr Lecter is still staring at Will in a frank, unabashed way; and Will is now trying not to catch the latter’s eye by looking at Mary instead, despite the fact she’s not doing anything of particular note beyond standing against the wall with her hands neatly clasped in front of her apron. It’s the type of trim, orderly stance that Will suspects is probably taught to domestics as standard (he can already imagine a matronly housekeeper instructing the maids in deportment: “spick and span at all times!”) but nevertheless she still manages to look vaguely slovenly in comparison to Dr Lecter, who has all the poise and posture of a bit of Grecian sculpture in the British Museum. There’s a short silence, and Will tries to move away before realising he’s hemmed in on all sides and there isn’t really anywhere to go.

“Is there somewhere we could talk privately?” he finally says, in a vague attempt at regaining some influence over the situation, if not over himself as well.

“Yes, of course,” comes the smooth reply. Where is that accent from? “Come through to the consulting room. Mary, no visitors for the next hour if you please.” The latter performs a neat curtsey and withdraws and Will, who is unused to such displays of obsequiousness, can’t help internally sneering at it. Nevertheless he still follows behind Dr Lecter dutifully enough, and has to remind himself that he is a member of The Socialistic Labor Party (admittedly in secret, but even so) and has read The Communist Manifesto as well as Discourse on Inequality (both currently in his trunk with emphatic underlining, exclamation marks, and pencilled notes in the margins) and is not about to perform the male equivalent of curtseying for anyone. Dr Lecter moves rather elegantly for someone so tall, but also quickly, and Will hastens his own pace so as to leave no suspicions that he is maintaining a respectful distance (or, potentially even worse, is lagging behind on the basis of having somewhat shorter legs). Owing to the appellation of ‘consulting room,’ he’s expecting to be taken somewhere confined and clinical; and is once again somewhat surprised to be lead into a sumptuously-appointed apartment full of gleaming wood and richly jewel-toned fabrics of ruby, amethyst and sapphire, as well as an entire floor of books whose shelves are accessible only by a ladder. Books are expensive; hardly anyone he knows possesses a substantial number of them, and beyond a visit to the congressional library during a brief placement in Washington he’s never seen so many together in a single place. He gazes at the display, somewhat overawed.

“Inspector Graham?”